By Nat Lownes, DATA Lab Software Engineer, and Kate Kelly, DATA Lab Content Manager

50 years ago, the Philadelphia Inquirer published results from the first-ever computer analysis of criminal legal data to be conducted by a newspaper. This very likely was the first time that Philadelphians had seen statistics used to assess the functions of their local court system, thanks to recent advances in computer technology. The 1972 analysis revealed unfair treatment of Black Philadelphians by prosecutors and judges, and the article series represents an interesting juncture in the Inquirer’s effort to reckon with its own problematic reporting on racial injustice. It would be another 45 years before Philadelphians gained regular access to data on criminal cases: in 2019, DA Larry Krasner launched a public data dashboard and a new unit called the District Attorney’s Transparency Analytics (DATA) Lab, allowing for external assessment and scrutiny of an important public office.

The Inquirer’s historical data was compiled over a seven-month investigation in 1972, during which reporters gathered information on the previous year’s criminal cases to be entered into a computer and analyzed. The findings were published in a February 1973 article series titled “Crime and Injustice,” and were followed by Inquirer articles recommending specific reforms. The dataset now lives in the archives of University of North Carolina’s Dataverse, available for public download and exploration. Records kept by District Attorney Arlen Specter and preserved at the Philadelphia City Archives show how the 1973 District Attorney’s Office reacted internally to the Inquirer’s reporting, including which reforms were pursued.

Data can help move institutions to make necessary changes, but many agencies lack the information management systems and processes needed to easily assess their own work. The Inquirer’s pioneering data work led to criticisms of the 1973 District Attorney’s Office and the city’s judges, but it would take decades for public accountability to develop. The efforts of the journalists, archivists, and librarians who created, preserved, and digitized this information, further allow the opportunity to reflect on a half-century of efforts to assess and improve Philadelphia’s criminal legal system.

The “Crime and Injustice” Investigative Series

Throughout 1972, Philadelphia Inquirer investigative journalists Donald Barlett and James Steele examined case records, reports, and testimony for more than 19,000 indictments issued during 1971 for four major crimes of violence – murder, rape, aggravated robbery, and aggravated assault. Their final dataset included 1,374 cases involving 1,034 defendants, with data points that included bail, disposition, and sentencing. Analyzed by what was then-new computer technology, the cases in the dataset represent a 39% sampling of all persons indicted in 1971 for one of the four major crimes.

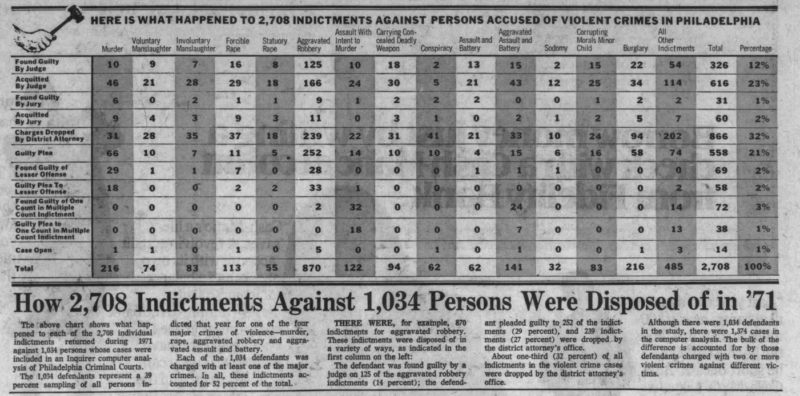

The “Crime and Injustice” articles ran in early 1973, over the week of February 18th to February 24th. Each day, the series focused on a different facet of the criminal legal system: the judiciary, the district attorneys, disparate case outcomes, and inconsistencies in the bail system. The article series presented Philadelphians with information about their justice system publicly, in plain language, and with some transparency around methodology. The following table published in the Philadelphia Inquirer on February 22nd, 1973, displays case outcomes in a way that is similar to today’s DAO Public Data Dashboard.

From the Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 22, 1973

The series highlighted inequalities across Philadelphia’s criminal legal system, with stories such as “Equal Justice for All?…Not in Philadelphia’s Courts” and “Public Officials Keep Alive the Myth of ‘Equal Justice’.” A few paragraphs in to the first story of the series, the Inquirer journalists offered this overall assessment of Philadelphia’s criminal courts: “It is a system that really is no system at all and it has very little to do with justice.” Using data, the Inquirer articles described what is now known to be longstanding, systemic racial disparities in Philadelphia’s criminal courts. Reporting showed that for the same serious offenses:

- Black defendants were given probation at a rate of 36% versus 58% for white defendants;

- Black defendants who pleaded guilty or were convicted of a serious crime were sentenced to jail in 64% of cases, versus 42% for white defendants;

- Black defendants were held without bail at almost twice the rate of white defendants and white defendants were released on their own recognizance at a rate 4 times greater than that of Black defendants.

The third day of the article series focused on the District Attorney’s Office (DAO) with a front-page story titled, “DA Churns Out Indictments…But Many Are Weak.” The data showed that defendants were found innocent on 3 of every 12 indictments and convicted or plead guilty on 5 of every 12 indictments. The Inquirer also published a table of metrics for each Assistant District Attorney, with their individual rates of conviction, cases dropped, probation, and length of jail sentence. A time-to-trial metric was tracked by the DAO as an average number of days between the preliminary hearing and trial. According to the 1971 DAO’s annual report, it was just under 130 days; the Inquirer’s data analysis found 175 days. Today, the DAO measures case-length as days from arrest to disposition, which more completely captures all the steps of the criminal legal process to better identify how long individuals are in contact with the system due to a given case. “Case Length” data is available on the Public Data Dashboard.

The articles and data findings contained a harsh rebuke of their work, and the 1973 DAO staff immediately reacted to the Inquirer’s reporting. District Attorney Arlen Specter sent an office-wide memo which read in part: “I do not want you to be unduly concerned about the article in this morning’s Inquirer, because we can decimate their charges.” The office took issue with the statistical methods used to calculate rates of conviction, estimation of Assistant District Attorney workload, and other aspects. The memorandum promised a forthcoming “detailed, line-by-line analysis of the Inquirer article,” but did not dispute any of the Inquirer statistics regarding racial disparities.

Nearly a month after the initial articles were published, on March 18th, 1973, the Inquirer issued new stories with the headlines “Other Cities Show Way for Philadelphia Courts” and “Public Is Kept in Dark About Courts.” This follow-up reporting suggested several reforms for Philadelphia’s criminal legal system:

- adopt an “individual judge calendar”

- standardize record keeping

- appoint a court administrator

- set an 11-week maximum time limit from arrest to trial

- liberalize bail setting policies

- compensation for victims

- limit court appeals

- abolish separate trials in homicide cases

- provide the public information with information on how the system is functioning

- screen out weak and frivolous cases

- divert less serious cases to the Municipal Court

- establish procedures to review sentencing to avoid disparities

The Inquirer concluded that “No large city court system in the country, though, is in need of more basic reform than Philadelphia’s.” The entire “Crime and Injustice” series was reprinted for Inquirer readers that week. Later that year, District Attorney Arlen Specter lost his reelection to Democrat Emmett Fitzpatrick, who had been endorsed by the Philadelphia Inquirer.

50 Years Later, What Has Changed?

Many of the reforms suggested by the Inquirer were implemented in the following decades, some more quickly than others. Historical research and an interview with First Assistant District Attorney Carolyn Engel Temin, a longtime Philadelphia legal practitioner and former judge, reveals how these system changes unfolded in the subsequent decades. The individual judge calendar was a top issue nationally and in Philadelphia’s 1974 judicial elections. Joint trials in homicide cases were permitted under Act 213 of 1976. In June 1973, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court adopted Rule 1100 which stated that a defendant must be brought to trial in 180 days. In 1978 the Pennsylvania Commission on Sentencing was established by the General Assembly to “promote fairer and more uniform sentencing throughout the Commonwealth.”

Some reforms were staunchly resisted, and would not be enacted until almost 50 years after the Inquirer’s reporting. The 1970s and 1980s were characterized by a reactionary toughening of criminal legal policies, largely driven by white supremacist backlash to Civil Rights movement victories of the 1960s. The new tough-on-crime laws put more people in jail for longer, leading to mass incarceration and hindering the implementation of a rehabilitative approach to justice.

The harms and costs created by mass incarceration forced justice actors of all perspectives to make changes. Diversion programs have been expanded in Philadelphia over the last few decades, and more legal practitioners realize the ineffectiveness of criminalizing addiction. Under the current administration, the Conviction Integrity Unit (CIU) has been better-resourced, increasing capacity to investigate unjust sentencing and wrongful convictions. The CIU and DAO Law Division have facilitated 29 exonerations since 2018. Criminal-legal system stakeholders increasingly acknowledge the harms of traditional carceral practices and embrace updated, evidence-based practices that reduce those harms while also reducing law-breaking and promoting community safety.

One important recommendation made by the Inquirer in 1973 was that criminal legal officials make information about the system and its functions available to the residents of the jurisdiction. Historical datasets such as the one compiled by the Inquirer are a rare chance to look back at Philadelphia’s court system at a point in time when little other data was available. Despite the popularity of tech-forward crime dramas, most criminal legal jurisdictions suffer from outdated technology, a lack of quality data, and inability to quickly quantify their own work. Efforts to update and integrate jail management and case management systems have met costly challenges.

In 2019, this office launched a data dashboard with detailed reports on charges, bail, case outcomes, case disposition times, future years of incarceration, and more. This dashboard is maintained by the District Attorney’s Transparency Analytics (DATA) Lab, which works with researchers and community partners to share data and findings. The Philadelphia DAO is one of the few public prosecutor’s offices around the country that maintains a public data dashboard, and will continue to build on a history of progress towards better data transparency. While investigative journalists are essential in holding public institutions accountable, those same offices should create and maintain their own data systems and make the findings available and accessible to the community.

Explore the Data

The Inquirer dataset is a valuable asset in placing today’s data in a historical context. In 2018, DA Larry Krasner issued a policy to stop asking for low cash bail amounts under the belief that no one should be held on a low dollar amount such that only people with very little money or income would be unable to pay and get released. Looking back at the past ten years helps assess how this policy has impacted the proportional distribution of bail outcome types, while a 50-year look back offers even more context.

Below is a chart of bail categories, which combines the Inquirer’s 1971 dataset with data from 2011 through 2021 to show bail patterns for the four serious offense types. The bars show proportions of different bail outcomes for the given year, including different bail amounts, held without bail, and released on own recognizance. One dramatic difference in the historical data is how many defendants were held without bail; 39% of the 1971 sample versus 9% in 2021. When filtering by defendant race, the 1971 release rate for white defendants (9.3%) is nearly equal to the rate in 2019. For Black defendants the 1971 release rate of 1.5% is almost identical to the 2015 rate of 1.7%. The release rate for Black defendants began to trend upward in 2015, with more significant yearly increases since 2018. Progress is visible, but the outcomes for defendants of different races remain unequal.

Bail Outcomes for Four Serious Charges: Murder, Rape, Aggravated Robbery, and Aggravated Assault

People released on their own recognizance for these charges may still be subjected to pre-trial supervision and reporting requirements.

Join the DAO DATA Lab mailing list to stay up to date with our ongoing analysis and research within the Philadelphia criminal legal system.