By Mikayla Smith, Research Assistant, DAO DATA Lab

Casey Morrison and Lauren Laino, Research Interns, DAO DATA Lab

Prosecutors utilize discretion when they decide whether or not to file charges, the type of charges to file, the cases for which they will seek to negotiate pleas, and what concessions to offer. All of these decisions impact case outcomes, and Philadelphians. Roughly 95 percent of all convictions are the result of a guilty plea negotiated between prosecutors and defense attorneys, agreed to first by the defendant, and then accepted by a judge. Yet far less is known about plea bargaining than the trials that dominate news and popular culture portrayals of criminal legal proceedings. Lack of insight into plea bargaining practices is in part due to the lack of research on prosecution more broadly, as prosecutorial offices have not historically been open to external scrutiny or valued using research and data to inform practice, or the transparency, knowledge, and accountability that come with it. Here we describe some of what the Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office is doing to address the “black box” of black boxes: plea bargaining.

The Philadelphia District Attorney’s Office and District Attorney’s Transparency Analytics (DATA) Lab has been working closely with The Urban Institute to investigate plea bargaining and to review a sample of cases resolved through plea. In addition to analyzing data collected through a case file review, the Urban Institute research involves interviews with Assistant District Attorneys (ADAs), ADA surveys, and a quantitative analysis. The City of Philadelphia’s participation in the MacArthur Foundation’s Safety and Justice Challenge (SJC) has allowed for this data to be shared through the Institute for State and Local Governance.

Determining the extent to which prosecutorial practices influence outcomes through research can ensure greater equality and fairness within the criminal legal system. By participating in this research, our ADAs and research staff acknowledge that fair, progressive prosecution requires introspection, transparency, and independent evaluation.

Conducting a Case File Review to Inform Independent Research

In May and early June of 2022, we engaged in a thorough case-coding process. The Urban Institute provided the DATA Lab with a random sample of about 200 files, from 2014 to 2019, which we ordered from archives. Since, we have systematically coded details of interest in a spreadsheet, including but not limited to key charges, plea offer outcomes, detainment statuses, and defendants’ prior records. In addition to coding information, we have cross-checked case management systems and collected up-to-date records to ensure accurate metrics. All of this work was necessary because the DAO does not have an integrated case management system due to historical underinvestment in technology. Instead, DAO personnel utilize paper files for each case, and a series of information management systems maintained by different agencies. The amassed research data will be de-identified before being provided to the Urban Institute, which will also maintain anonymity for ADA interviews and surveys.

We coded these case files in preparation for an objective analysis that will be performed by the Urban Institute team. By analyzing the metrics that we have provided, the Urban Institute will be able to discern if any racial disparities exist and, if so, understand what is contributing to them. This external review by an independent nonprofit organization will provide us with honest analyses about our office’s plea-bargaining practices. Urban Institute’s final report will leave us better equipped to make any necessary structural improvements.

Identifying and Confronting Racial Disparities

Much evidence suggests that defendant demographics have an impact on prosecutors’ decisions. For example, a 2016 study of misdemeanor drug cases in New York City found that Black and Latino defendants are more likely to receive charge bargains that involve pleading to the current charge as opposed to a reduced charge, resulting in a greater likelihood that they receive jail terms. Further, white defendants in Wisconsin were found to be 25 percent more likely to have their initial charge reduced to a lesser crime or even dropped completely. We must determine whether similar disparities are present in Philadelphia’s criminal justice system, so that we may remedy them.

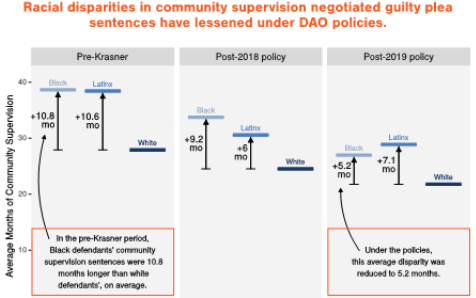

With such research in mind, sentencing policies implemented under District Attorney Krasner in 2018 and 2019 guided ADAs to make better plea offers to reduce disparities and harmfully long periods of probationary supervision. This was achieved in part by reducing discretion that may lead to disparities in plea– bargained sentences. Our April 2021 report on Ending Mass Supervision shows that, following the implementation of these policies, “median community supervision sentence lengths decreased 25% for sentences reached through negotiated guilty pleas.” Critically, the new DAO Sentencing Policies reduced median community supervision lengths from negotiated pleas for Black, Latino, and white defendants, while reducing overall racial disparities in supervision sentencing. Independent research by the Urban Institute will inform how we can continue to improve equity and outcomes.

Graphic from page 17 of Ending Mass Supervision report

The above findings underscore the importance of focusing on race and ethnicity when examining the plea-bargaining process and prosecutorial discretion—something that Urban aims to do with the new data available because of our case file review, combined with responses from ADAs and administrative data from ISLG. Decisions that prosecutors make regarding how to proceed with a defendant’s case have many implications for final punishment outcomes—some of which could be unjust. It is important that our office examines this relationship directly in order to determine how race and ethnicity may influence prosecutors’ life-altering decisions.